A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O

P Q R S T U

V W X

Y Z

A

Ablepsy - Blindness

Ague - Malarial Fever

American plague - Yellow fever

Anasarca - Generalized massive edema

Aphonia - Laryngitis

Aphtha - The infant disease "thrush"

Apoplexy - Paralysis due to stroke

Asphycsia/Asphicsia - Cyanotic and lack of oxygen

Atrophy - Wasting away or diminishing in size.

B

Bad Blood - Syphilis

Bilious fever - Typhoid, malaria, hepatitis or elevated temperature and bile emesis

Biliousness - Jaundice associated with liver disease

Black plague or death - Bubonic plague

Black fever - Acute infection with high temperature and dark red skin lesions and high mortality rate

Black pox - Black Small pox

Black vomit - Vomiting old black blood due to ulcers or yellow fever

Blackwater fever - Dark urine associated with high temperature

Bladder in throat - Diphtheria (Seen on death certificates)

Blood poisoning - Bacterial infection; septicemia

Bloody flux - Bloody stools

Bloody sweat - Sweating sickness

Bone shave - Sciatica

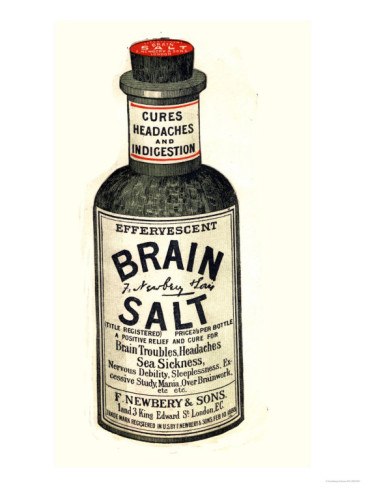

Brain fever - Meningitis

Breakbone - Dengue fever

Bright's disease - Chronic inflammatory disease of kidneys

Bronze John - Yellow fever

Bule - Boil, tumor or swelling.

Jump to Alphabet

Jump to Table of Contents

C

Cachexy - Malnutrition

Cacogastric - Upset stomach

Cacospysy - Irregular pulse

Caduceus - Subject to falling sickness or epilepsy

Camp fever - Typhus; aka Camp diarrhea

Canine madness - Rabies, hydrophobia

Canker - Ulceration of mouth or lips or herpes simplex

Catalepsy - Seizures / trances

Catarrhal - Nose and throat discharge from cold or allergy

Cerebritis - Inflammation of cerebrum or lead poisoning

Chilblain - Swelling of extremities caused by exposure to cold

Child bed fever - Infection following birth of a child

Chin cough - Whooping cough

Chlorosis - Iron deficiency anemia

Cholera - Acute severe contagious diarrhea with intestinal lining sloughing

Cholera morbus - Characterized by nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps,elevated temperature, etc. Could be appendicitis

Cholecystitus - Inflammation of the gall bladder

Cholelithiasis - Gall stones

Chorea - Disease characterized by convulsions, contortions and dancing

Cold plague - Ague which is characterized by chills

Colic - An abdominal pain and cramping

Congestive chills - Malaria

Consumption - Tuberculosis

Congestion - Any collection of fluid in an organ, like the lungs

Congestive chills - Malaria with diarrhea

Congestive fever - Malaria

Corruption - Infection

Coryza - A cold

Costiveness - Constipation

Cramp colic - Appendicitis

Crop sickness - Overextended stomach

Croup - Laryngitis, diphtheria, or strep throat

Cyanosis - Dark skin color from lack of oxygen in blood

Cynanche - Diseases of throat

Cystitis - Inflammation of the bladder

D

Day fever - Fever lasting one day; sweating sickness

Debility - Lack of movement or staying in bed

Decrepitude - Feebleness due to old age

Delirium tremens - Hallucinations due to alcoholism

Dengue - Infectious fever endemic to East Africa

Dentition - Cutting of teeth

Deplumation - Tumor of the eyelids which causes hair loss

Diary fever - A fever that lasts one day

Diptheria - Contagious disease of the throat

Distemper - Usually animal disease with malaise, discharge from nose and throat, anorexia

Dock fever - Yellow fever

Dropsy - Edema (swelling), often caused by kidney or heart disease

Dropsy of the Brain - Encephalitis

Dry Bellyache - Lead poisoning

Dyscrasy - An abnormal body condition

Dysentery - Inflammation of colon with frequent passage of mucous and blood

Dysorexy - Reduced appetite

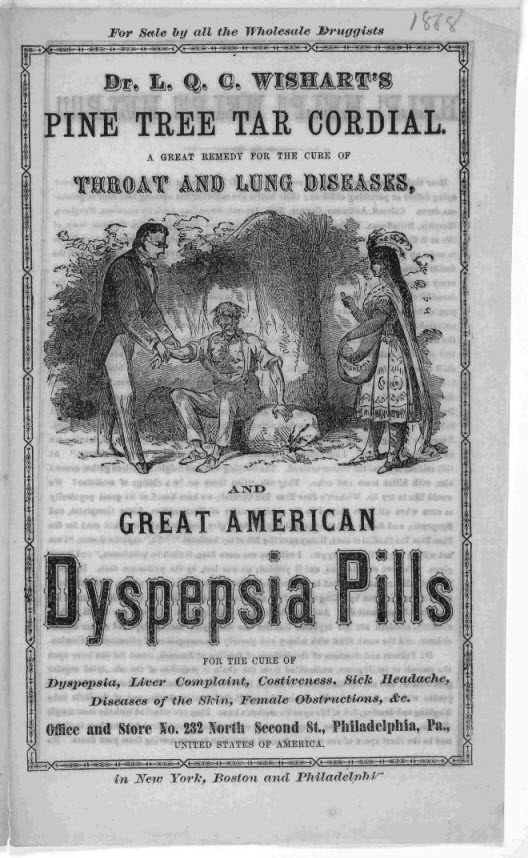

Dyspepsia - Indigestion and heartburn. Heart attack symptoms

Dysury - Difficulty in urination

Jump to Alphabet

Jump to Table of Contents

E

Eclampsy - Symptoms of epilepsy, convulsions during labor

Ecstasy - A form of catalepsy characterized by loss of reason

Edema - Nephrosis; swelling of tissues

Edema of lungs - Congestive heart failure, a form of dropsy

Eel thing - Erysipelas

Elephantiasis - A form of leprosy

Encephalitis - Swelling of brain; aka sleeping sickness

Enteric fever - Typhoid fever

Enterocolitis - Inflammation of the intestines

Enteritis - Inflations of the bowels

Epitaxis - Nose bleed

Erysipelas - Contagious skin disease, due to Streptococci with vesicular and bulbous lesions

Extravasted blood - Rupture of a blood vessel

F

Falling sickness - Epilepsy

Fatty Liver - Cirrhosis of liver

Fits - Sudden attack or seizure of muscle activity

Flux - An excessive flow or discharge of fluid like hemorrhage or diarrhea

Flux of humour - Circulation

French pox - Syphilis

G

Gathering - A collection of pus

Glandular fever - Mononucleosis

Great pox - Syphilis

Green fever / sickness - Anemia

Grippe/grip - Influenza like symptoms

Grocer's itch - Skin disease caused by mites in sugar or flour

H

Heart sickness - Condition caused by loss of salt from body

Heat stroke - Body temperature elevates because of surrounding environment temperature and body does not perspire to reduce temperature. Coma and death result if not reversed

Hectical complaint - Recurrent fever

Hematemesis - Vomiting blood

Hematuria - Bloody urine

Hemiplegy - Paralysis of one side of body

Hip gout - Osteomylitis

Horrors - Delirium tremens

Hydrocephalus - Enlarged head, water on the brain

Hydropericardium - Heart dropsy

Hydrophobia - Rabies

Hydrothroax - Dropsy in chest

Hypertrophic - Enlargement of organ, like the heart

Jump to Alphabet

Jump to Table of Contents

I

Impetigo - Contagious skin disease characterized by pustules

Inanition - Physical condition resulting from lack of food

Infantile paralysis - Polio

Intestinal colic - Abdominal pain due to improper diet

J

Jail fever - Typhus

Jaundice - Condition caused by blockage of intestines

K

King's evil - Tuberculosis of neck and lymph glands

Kruchhusten - Whooping cough

L

Lagrippe - Influenza

Lockjaw - Tetanus or infectious disease affecting the muscles of the neck and jaw. Untreated, it is fatal in 8 days

Long sickness - Tuberculosis

Lues disease - Syphilis

Lues venera - Venereal disease

Lumbago - Back pain

Lung fever - Pneumonia

Lung sickness - Tuberculosis

Lying in - Time of delivery of infant

M

Malignant sore throat - Diphtheria

Mania - Insanity

Marasmus - Progressive wasting away of body, like malnutrition

Membranous Croup - Diphtheria

Meningitis - Inflations of brain or spinal cord

Metritis - Inflammation of uterus or purulent vaginal discharge

Miasma - Poisonous vapors thought to infect the air

Milk fever - Disease from drinking contaminated milk, like undulant fever or brucellosis

Milk leg - Post partum thrombophlebitis

Milk sickness - Disease from milk of cattle which had eaten poisonous weeds

Mormal - Gangrene

Morphew - Scurvy blisters on the body

Mortification - Gangrene of necrotic tissue

Myelitis - Inflammation of the spine

Myocarditis - Inflammation of heart muscles

N

Necrosis - Mortification of bones or tissue

Nephrosis - Kidney degeneration

Nepritis - Inflammation of kidneys

Nervous prostration - Extreme exhaustion from inability to control physical and mental activities

Neuralgia - Described as discomfort, such as "Headache" was neuralgia in head

Nostalgia - Homesickness

Jump to Alphabet

Jump to Table of Contents

P

Palsy - Paralysis or uncontrolled movement of controlled muscles. It was listed as "Cause of death"

Paroxysm - Convulsion

Pemphigus - Skin disease of watery blisters

Pericarditis - Inflammation of heart

Peripneumonia - Inflammation of lungs

Peritonotis - Inflammation of abdominal area

Petechial Fever - Fever characterized by skin spotting

Puerperal exhaustion - Death due to child birth

Phthiriasis - Lice infestation

Phthisis - Chronic wasting away or a name for tuberculosis

Plague - An acute febrile highly infectious disease with a high fatality rate

Pleurisy - Any pain in the chest area with each breath

Podagra - Gout

Poliomyelitis - PolioPotter's asthma - Fibroid pthisis

Pott's disease - Tuberculosis of spine

Puerperal exhaustion - Death due to childbirth

Puerperal fever - Elevated temperature after giving birth to an infant

Puking fever - Milk sickness

Putrid fever - Diphtheria.

Q

Quinsy - Tonsillitis.

Jump to Alphabet

Jump to Table of Contents

R

Remitting fever - Malaria

Rheumatism - Any disorder associated with pain in joints

Rickets - Disease of skeletal system

Rose cold - Hay fever or nasal symptoms of an allergy

Rotanny fever - (Child's disease) ???

Rubeola - German measles

S

Sanguineous crust - Scab

Scarlatina - Scarlet fever

Scarlet fever - A disease characterized by red rash

Scarlet rash - Roseola

Sciatica - Rheumatism in the hips

Scirrhus - Cancerous tumors

Scotomy - Dizziness, nausea and dimness of sight

Scrivener's palsy - Writer's cramp

Screws - Rheumatism

Scrofula - Tuberculosis of neck lymph glands. Progresses slowly with abscesses and pistulas develop. Young person's disease

Scrumpox - Skin disease, impetigo

Scurvy - Lack of vitamin C. Symptoms of weakness, spongy gums and hemorrhages under skin

Septicemia - Blood poisoning

Shakes - Delirium tremens

Shaking - Chills, ague

Shingles - Viral disease with skin blisters

Ship fever - Typhus

Siriasis - Inflammation of the brain due to sun exposure

Sloes - Milk sickness

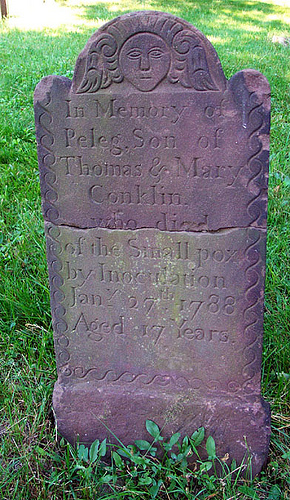

Small pox - Contagious disease with fever and blisters

Softening of brain - Result of stroke or hemorrhage in the brain, with an end result of the tissue softening in that area

Sore throat distemper - Diphtheria or quinsy

Spanish Disease - Syphilis

Spanish influenza - Epidemic influenza

Spasms - Sudden involuntary contraction of muscle or group of muscles,like a convulsion

Spina bifida - Deformity of spine

Spotted fever - Either typhus or meningitis

Sprue - Tropical disease characterized by intestinal disorders and sore throat

St. Anthony's fire - Also erysipelas, but named so because of affected skin areas are bright red in appearance

St. Vitas dance - Ceaseless occurrence of rapid complex jerking movements performed involuntary

Stomatitis - Inflammation of the mouth

Stranger's fever - Yellow fever

Strangery - Rupture

Sudor anglicus - Sweating sickness

Summer complaint - Diarrhea, usually in infants caused by spoiled milk

Sunstroke - Uncontrolled elevation of body temperature due to environment heat. Lack of sodium in the body is a predisposing cause

Swamp sickness - Could be malaria, typhoid or encephalitis

Sweating sickness - Infectious and fatal disease common to UK in 15th century

T

Tetanus - Infectious fever characterized by high fever, headache and dizziness

Thrombosis - Blood clot inside blood vessel

Thrush - Childhood disease characterized by spots on mouth, lips and throat

Tick fever - Rocky mountain spotted fever

Toxemia of pregnancy - Eclampsia

Trench mouth - Painful ulcers found along gum line, Caused by poor nutrition and poor hygiene

Tussis convulsiva - Whooping cough

Typhus - Infectious fever characterized high fever, headache, and dizziness

V

Variola - Smallpox

Venesection - Bleeding

Viper's dance - St. Vitus Dance

W

Water on brain - Enlarged head

White swelling - Tuberculosis of the bone

Winter fever - Pneumonia

Womb fever - Infection of the uterus.

Worm fit - Convulsions associated with teething, worms, elevated temperature or diarrhea

Y

Yellowjacket - Yellow fever.

![]() Disease & Death in Early America

Disease & Death in Early America